How many calories does a gymnast need (and does it matter?)

explore the blog

free training

The Podcast

Learn to fuel the gymnast for optimal performance and longevity in the sport.

How to Fuel the Gymnast

Learn how to fuel your gymnast so that you can avoid the top 3 major nutrition mistakes that keep most gymnasts stuck, struggling, and injured.

looking for...?

There are two groups of people. Those who think “calories don’t count” and those who think they do count. Add in the confusion re how many calories gymnasts need, and it gets really fuzzy. I’m here to tell you that calories DO count from a physiological perspective, but the “calories in, calories out” equation is more complicated than a simple balance sheet.

Parents of gymnasts (and sometimes the gymnasts themselves) often worry their gymnast is not eating enough calories. I’ll hear things like “oh, don’t worry about the calories, but do make sure she stays on the growth chart”. Or “don’t focus on calories as they can be ‘empty’, focus on healthy options”.

What matters most for growth and development?

While these statements are not entirely incorrect, this is what matters for your gymnast’s growth and development:

- Calories do count, but it doesn’t mean you have to count them. Children are typically very good at regulating their eating and responding to hunger/fullness cues. But, high level athletes (especially under 18) can easily get distracted, not notice hunger cues due to long practices in and around normal meals and snacks, etc. I see it time and time again. Gymnasts with stunted growth after years of unintentional under fueling.

I’m not advocating you or your gymnast count calories. But checking in with a sports dietitian to see where they’re at and comparing growth history, performance, injury status, etc. are all important aspects of evaluating adequacy of fueling.

- “Healthy food” does not equal “adequate fueling”. Just because what your gymnast is eating is healthy doesn’t mean it’s meeting her energy needs (calories which come from carbohydrates, protein, and fat). You can eat “healthfully” and overeat, undereat, or meet your needs. It’s all about context.

Do calories even matter?

In short, yes.

First off, we have to understand a calorie. Calorie is a measure of heat. Specifically how much heat is needed to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1 degree Celsius.

To figure out how many calories a food has, a scientist will blow up the food in what’s call a “bomb calorimeter” and measure how much heat it gives off.

Here’s the thing. We don’t always know how many calories a given food has. The USDA allows for up to 20% error on food labels, so that piece of bread that says 80 calories could have anywhere from 64 to 96 calories.

Calorie absorption in the body

Secondly, we don’t always know how many calories of a food are actually absorbed by the body. We have research studies that show the more processed a food is, the more calories are absorbed (like peanut butter vs peanuts). This makes sense, as the more processed the food is (cooked, ground, etc), the easier it is for the body to digest.

There is something called the “thermic effect of food”. This is the energetic (caloric) “cost” of digesting and metabolizing (using) a food. Protein (meat, chicken, eggs, beef, fish, etc) has a TEF of about 10%, which means of the 120 calories in a 3 oz piece of chicken breast, ~12 calories will be used by the body to break the protein down into a useable fuel source, amino acids which are the most basic building blocks of protein.

So, while counting and tracking calories is not an exact science, when working with a high level athletes I can usually get a very strong idea of whether or not a gymnast (on average) is getting the calories they need for growth, development, and performance.

So how many calories does a high level gymnast need?

When I refer to a high level gymnast, I’m speaking about those practicing at least 15-20 hrs a week. They could range from 7 to 22 years old. So obviously I’m going to need to break down average energy requirements based on age (though this varies highly with body weight). For all intents and purposes, I’m going to focus on gymnasts that are 12-18 years old.

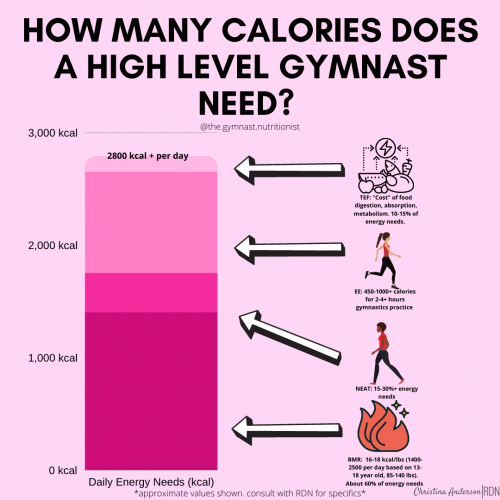

When we look at the caloric needs of an individual, we have to separate these needs into four parts:

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)– This is how many calories an individual needs at rest, i.e. lying in bed all day. This represents the energy required by the brain, heart, lungs, and other organs to function. As well as support normal growth and development. BMR is about 60% of total energy needs and around 12-14 kcal/lbs for a 13 to 18 year old that’s 85-140 lbs.

- Non-exercise Activity Thermogenesis- This is the energy used while moving around, walking to and from the kitchen or classroom, fidgeting, etc. This varies highly amongst individuals and during different life seasons, etc. This represents 15-30% total energy required.

- Thermic Effect of Food-As I mentioned earlier, this is the “cost” of digesting and metabolizing our food. It is not huge contributor to daily energy requirements, but it’s there. Smallest percentage of total energy needs, about 10-15%.

- Exercise Expenditure-Obviously this has the most variance between individuals. The gymnast is estimated to expend anywhere from 400-900+ calories during a 3+ hour training session. This is where Performance Nutrition comes in. How we make sure we’re giving the gymnast what they need to optimally fuel their activity and recover. Which is in addition to normal nutrition needs.

- Injury recovery also represents part of this equation, especially for an athlete. Injury recovery can require 15-50% more calories than normal (surgical wound vs burn, etc).

BMR Testing

The best way to test someone’s BMR is through indirect calorimetry or measuring gas exchange between exhaled carbon dioxide and inhaled oxygen. The machines used to measure this, called a “metabolic cart”, cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. And are only going to be found in research labs, elite sports performance centers, and hospitals.

In my experience, there are a lot of things we can address with an athlete’s nutrition while using predictive equations versus needing to do indirect calorimetry. Which has a margin of error just like any other kind of testing (bodyfat, etc).

When calculating total energy needs, you have to factor in each part of the equation, not just BMR and exercise expenditure.

How do I know if my gymnast is eating enough?

“Enough” is highly subjective and cannot always be trusted by appetite alone, especially for the high level gymnast. Exercise blunts appetite and practice schedules often span several meals/snacks throughout the day, so it’s very easy for the gymnast to be chronically under-fueled.

Before counting calories (Might I suggest allowing a registered dietitian sports nutritionist to do this for you), here are some things to look at:

Growth trends

Oh, I love growth charts. As a board certified pediatric and adolescent dietitian nutritionist, growth charts are my favorite. They tell us a story that we often don’t realize exists. For the gymnast (and all other children/adolescents), we want consistent growth along “their curve”. Growth charts are separated into curves or “isopleths” that are delineated as the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th “percentiles”. At about 6 months of age, infants will settle into “their” growth curve which could be the 25th percentile or the 85th percentile. What’s normal for one child is not necessarily normal for another.

We use the CDC 2-20 year old chart for females, and these charts are separated into a height, weight, and BMI curve. BMI is a product of comparing weight and height. It’s important to note that the BMI may be skewed for the high level athlete due to their body composition being higher in muscle than the general population.

It’s not that muscle weighs more than fat (5 pounds of muscle weighs the same as 5 pounds of fat tissue), but muscle is more dense and takes up less space. This means that your gymnast could be the same size as her sibling or peer, yet weigh more due to her body composition. Which is not a bad thing. Maintaining a healthy body composition is more important than weight for the athlete.

What we look for when looking at growth charts

We want to look at the charts to evaluate growth patterns and make sure the gymnast isn’t falling behind. Which typically happens with unintentional under fueling or intentional under fueling, i.e. disordered eating, etc. If your gymnast’s weight was always at the 75%tile and then fell to the 25-50%tile. This may not be normal for her and is a red flag that something is going on. Likewise, she may have tracked along the 50%tile until she hit puberty and then jumped to the 75%tile. Could be normal for HER or could represent that something is going on. Something like dieting due to not liking her post-pubertal body which can lead to binging and weight overshoot.

If you have concerns, go to your pediatrician and review the growth charts with them. Or send them to your registered dietitian.

Development/Menstruation Status

I won’t go into a ton of detail here as I’ve written about this in other posts. But if your gymnast has not started her period by 16, there is cause for concern. And don’t just assume it’s due to gymnastics.

The most common cause of delayed puberty in a gymnast is RED-S, relative energy deficiency in sport. This is a syndrome where an individual is not eating enough to support their energy needs. And thus impacting reproductive function, bone health, etc as there is not enough energy (calories) available to the body (intake – expenditure).

There are other reasons an athlete may not have started their period. But if they’re 16 and haven’t started or have started but are abnormal (missing periods, etc after the first year), this needs to be looked into. Normally you’d just see the OBGYN, but in the case of an athlete, a nutritional evaluation is prudent. More than likely they’re just not eating enough versus something else going on (PCOS, etc).

Injury Status/Recovery

If your gymnast has frequent injuries, especially stress and overuse injuries, this is a red flag that she’s likely not eating enough (RED-S). Again, another situation where it would be advisable to meet with a registered dietitian and get a good handle on her energy needs, performance nutrition, and appropriate growth goals.

Performance

Evaluating nutritional adequacy in the context of optimal performance is not always straightforward. Many of the high level gymnasts I work with don’t’ know how good they could feel until they start fueling properly. They don’t realize how much more energy they could have until they start eating and drinking enough in and around practice to support performance.

But, if your gymnast is having a hard time making it through 3+ hours of a workout. Or has trouble concentrating, low stamina, or is moody/emotional by the end of practice, these are all signs she may not be eating enough OR eating the right things at the right times.

Relationship with Food

How’s your gymnast actually doing with her nutrition? Is she able to enjoy all foods in moderation? Go out to eat without worry or anxiety? Or fuel herself before/during practice? A “no” to any of these questions (even if you just have some sneaking suspicions) is cause for concern and needs further evaluation. I will guarantee you that your gymnast is always struggling much more than you know. It’s not that you’re a bad parent or not “in-tune”. But food and body struggles are very personal and often cloaked in a lot of guilt/shame/embarrassment.

When should I be concerned about my gymnast’s nutrition?

You should be concerned if your gymnast has any of the red flags I’ve listed above. The first and simplest step would be to go to the pediatrician and check on growth. Make sure she’s following along her own curve and developing as she should. Endocrinology can also evaluate growth and development. They’ll check something called a “bone age” which is an x-ray of the arm to see if her bones match her chronological age (it should).

A “delayed bone age” is a sign of delayed growth that can be caused by a variety of things. However, the most likely culprit for the gymnast is RED-S. If she hasn’t gotten her period at she’s 16, it’s time to check in with the pediatrician and OBGYN to make sure there isn’t anything abnormal. She may also really benefit from sports RD consult. This can ensure your gymnast is getting the calories she needs as again this is the more likely reason a gymnast hasn’t started her period versus something else.

Need more help or support with fueling your gymnast? To learn more about making sure your gymnast is getting what she needs, check out The Balanced Gymnast® Program. This is exactly what we teach inside the program and our 1:1 coaching!

on the blog