explore the blog

free training

The Podcast

Learn to fuel the gymnast for optimal performance and longevity in the sport.

How to Fuel the Gymnast

Learn how to fuel your gymnast so that you can avoid the top 3 major nutrition mistakes that keep most gymnasts stuck, struggling, and injured.

looking for...?

Most gymnasts love protein because society (#dietculture) has deemed this fairly “safe”. There is a lot of misguided advice and false notion that “fat makes you fat” and “carbs make you fat”, which leaves protein as the more neutral of the three major macronutrients (carbs, protein, fat).

Here’s the deal, all three macronutrients play an essential role in the gymnast’s diet. Fat insulates nerves, cushions the major organs, and serves as the building blocks for appropriate hormone production (stress hormones, reproductive hormones, growth hormones). Carbohydrates (as we’ve discussed before in depth) is the “gymnast’s fuel”. Protein plays an essential role in the body, it serves as the building blocks for muscles, tendons, ligaments, and helps repair tissues.

There is a lot of uncertainty around how much of the pediatric/adolescent athlete’s diet should be made up of protein. And, there is a lot of misguided advice around how it’s used in the body and it’s role in exercise and performance. Continue reading to learn how much protein your gymnast really needs.

How much protein should be in the gymnast’s diet?

The “acceptable macronutrient distribution range” for protein is 10-35% total calories. Obviously this is quite the range, and most gymnasts will be on the lower end of this range in order to fit in adequate carbohydrate for proper fueling. Only 30-40% of the diet as carbohydrate would not be adequate for proper fueling. When I analyze the diets of my high level gymnasts, they often gravitate to about 30-40% protein, 30-40% carbohydrate, and 20-30% fat. While this may a solid macronutrient split for a sedentary individual, the higher protein content is displacing adequate carbohydrate without exceeding energy needs.

Percentages of macronutrients can be somewhat arbitrary, especially when the energy needs are high. Overall though, a 50-65% diet a carbohydrate, 25-30% fat, and 10-25% as protein would likely meet the needs of the high level gymnast (though this is not prescriptive and why I look at each athlete’s diet individually and calculate needs based on weight, age, injury status, goals, etc).

Protein is not “energizing”

Most gymnasts and parents I work with think that protein or fat is what gives “energy” during a workout. I’ll have gymnasts snacking on protein bars or mixed nuts in the middle of a 4+ hour workout and wonder why they’re still struggling to make it through.

Even when I worked in clinical outpatient nutrition, a lot of my patients with diabetes would think they needed more protein when they felt like they were having a low blood glucose episode, when in fact they needed carbohydrate (which breaks down into glucose).

While all calories are “energizing”, meaning they confer energy to the body, carbohydrates are what gives the quickest source of actual energy. In the middle of a 4+ hour workout, the athlete needs carbohydrate for more energy, not fat or protein as these break down too slowly for a timely benefit.

There’s a difference between eating for “hunger” vs performance. If your athlete is “starving” during practice, that’s a big sign that they’ve just not had enough to eat throughout the day.

High intensity, anaerobic sports like gymnastics use carbohydrate as the main fuel source. Protein and fat are both very “slow” fuel sources that take several hours to break down into a usable energy source in a sport like gymnastics. This is why I don’t like too much fat/protein in a pre-workout snack and recommend minimal if any protein during practice. It is helpful to have protein in the pre-workout snack as the protein will be broken down into it’s individual amino acids by the end of a 3-4 hour workout and they will be what it is available to the body to start the repair/recovery process.

Protein and Satiety (Fullness)

Protein does have a very impactful benefit in terms of making a meal or snack more filling or “satiating”. This is due to how protein is digested and causes the stomach to release hormones (chemical messengers) that tell the brain you’ve had nutrition.

This is why a Greek yogurt bowl with fruit and cereal will keep you full for a few hours versus just dry cereal (carbohydrate) or with a little milk (not adequate protein/fat).

I recommend pairing carbohydrates or fat at snacks with protein for some staying power and certainly want a protein source at all main meals.

Muscle protein synthesis

Protein amount and timing hinges upon “muscle protein synthesis”. Muscle protein synthesis and muscle protein breakdown are in constant flux and effected by physical activity and food intake. Both synthesis and breakdown are initiated by exercise, and repair of muscle damage and muscle growth are dependent on a positive muscle protein balance.

This process is dictated by adequate amounts of a specific amino acid called Leucine. This amino acid essentially “turns on” muscle protein synthesis or the process of building muscle. When an athlete wakes up in the morning, they are likely in a protein deficit or negative protein balance due to fasting overnight and the body doing it’s best to continue the repair and recovery process. This process can continue for 24-48 hrs after a workout, so it’s essential to make sure the body has the materials it needs.

It takes about 2-3 g of Leucine to maximally “turn on” muscle protein synthesis, and more is not better. About 3-4 oz of chicken, a scoop of whey protein, 3 eggs, or ¾ cup of Greek yogurt all have bout 2-3 g of leucine. Plant-based protein sources are lower in leucine and they also are missing some of the “essential” amino acids that the body must get from food as it can’t make them on it’s own. Plant-based proteins are also harder to digest and thus have less “anabolic” or muscle-building potential. This is why combining plant-based proteins appropriately and eating enough of the protein is essential for optimal muscle growth and adaptation to training. See here for more information on plant-based diets for gymnasts.

Protein quality

Proteins are graded on quality according to the “Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). Essentially this is an indicator of protein quality that takes into account the essential amino acid composition as well as digestibility. A protein cannot meet the body’s essential amino acids needs (you have to get from food, body can’t make) if the score is less than 100%.

Aside from soy protein isolate, all plant-based proteins have a PDCAAS score less than 100% due to either lower digestibility and/or a deficiency in certain essential amino acids.

Animal proteins sources like cow’s milk (with it’s whey/casein proteins), egg, chicken, pork, fish, have a 100% PDCAAS. Red meat is 92%.

Plant-based sources like black beans, lentils, cooked peas have a 60-75% PDCAAS. Pea protein concentrate (a common vegan protein option often added to food products in order to advertise “high protein) is 89% and the often touted “peanut butter is a great protein source” is 45%. Though plant-based protein sources may be rich in fiber and micronutrients, they have a lower muscle building potential which is essential for the high level gymnast.

As far a combining plant proteins, cereal proteins are deficient in lysine and legume (beans) are deficient in sulfur amino acids. Combine these foods and you’ll create a “complete” essential amino acid profile.

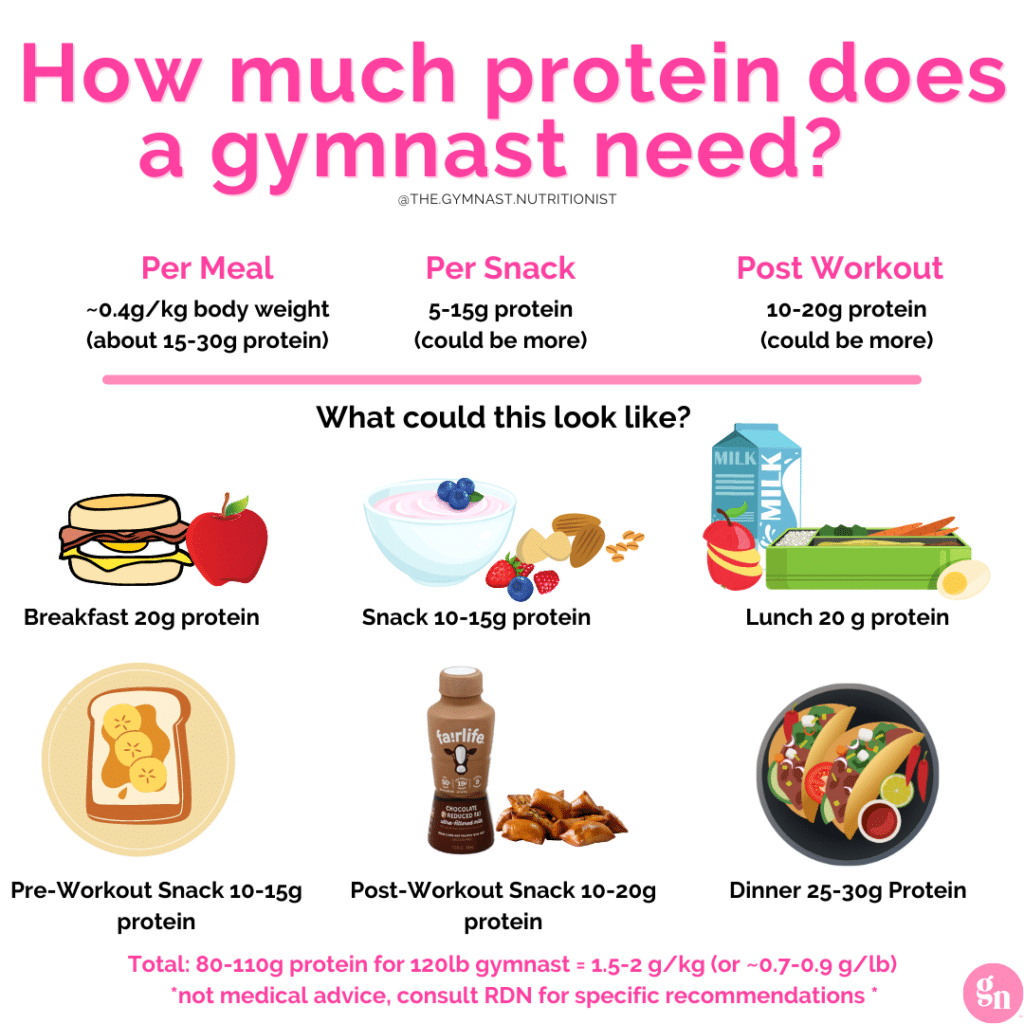

How much protein and how often

All of this talk about protein quality, muscle protein synthesis, and proteins role in skeletal health and performance leads us to the “how much” and “how often”.

You need a “protein feeding” even 3-5 hours to keep muscle protein synthesis and breakdown in balance (or in a surplus for those trying to build muscle).

This works out to 3 main meals (every 4-6 hours) with snacks sprinkled in between.

More is not better

Muscle protein synthesis is maximally stimulated at a dose of 0.31 g/kg of a high quality protein the proper leucine content (animal proteins). Eating more than this will result in the protein either been excreted or “wasted” in the sense of being used as an “expensive” fuel source.

Protein’s role in athletic performance

“Why do you say ‘no protein’ during a workout?” Because protein is a “slow” fuel. High intensity anaerobic sports like gymnastics rely on carbohydrate. Protein, fat, and fiber delay gastric emptying which will slow down the release of carbohydrate into the bloodstream which is not what we want during a high intensity workout where blood flow to the stomach is already limited.

Long, moderate endurance sports will sometimes pair carbohydrate with protein or fat but there is no benefit shown for sports like gymnastics. Read more here.

Pre-workout protein

Pre-workout protein can help to promote muscle protein synthesis and prevent a negative net protein balance from training.

As far as protein being used during exercise to improve performance, the data is not supportive. It may improve training efficiency, especially in long-endurance exercise at a moderate pace, but not high intensity intermittent sports like gymnastics. This is why I don’t recommend much if any protein intraworkout; the focus should be on easily digested carbohydrate.

Post-Exercise Protein

The goals for post-exercise nutrition are to refuel, rehydrate, and repair. Protein plays the essential role of providing the building blocks for repair and recovery. Ideally, the protein source would be a complete protein, rapidly digested/absorbed, and rich in Leucine. Milk and whey proteins best meet this criteria. Soy protein isolate contains less leucine, but would be the best vegan protein source. If there is a milk allergy or intolerance, I’d choose an egg white protein over soy due to higher bioavailability. One study looked at supplementing with cow’s milk, soy milk, or just carbohydrate on muscle growth in young men over 12 weeks and found the greatest muscle fiber growth in those who had the cow’s milk. This is a good thing for females as well; we want muscle growth as an adaption to the training stimulus.

Sports nutrition for post-exercise protein are largely generic, citing 20-40g of high quality protein (whey protein) to maximize recovery and muscle protein synthesis. This is problematic as there’s a big difference in need between a 115 lbs 14 year old gymnast and a 225 lbs 22 year old male gymnast.

To be more precise, studies support the recommendation of 0.24-0.31 g/kg protein post-exercise to support repair and recovery. For the 115 lbs gymnast, that’s just 12-16 g of protein which is much less than the generic 20-40g recommendation.

Pre-sleep protein

Sleep is a prolonged period without protein or exercise which are two of the stimuli for muscle protein synthesis. Pair that with the fact that sleep is a time where the body is trying to repair and recover from the previous day’s training and breakdown, it may be beneficial for the gymnast to consume pre-sleep protein to prevent this 7-10 hour negative net protein balance.

The recommendation is for 30-40 g of casein pre-sleep as casein is a “slower” protein that will digest throughout the night and provide a somewhat steady stream of amino acids (muscle building blocks) to help facilitate further repair/recovery. Casein, one of the main proteins in milk, is rich in Leucine.

Dispelling the “anabolic window”

We used to theorize that there was this “anabolic window” where protein had to be consumed within 30-60 minutes post-workout in order to “maximize the gains”. We’ve now found that this window may be as large as 24 hours following a workout, especially when the exercise is performed to failure (cannot do another rep).

Some gymnasts may need a post-workout snack with combined carbohydrate and protein and others may be fine just coming home to their next meal (likely dinner). If a gymnast has two-a-day workouts, this is another story. Aggressive refueling (carbohydrate), rehydration (fluids), and repair (protein) needs to take place between workouts, which may look like an immediate carbohydrate + protein recovery snack and then lunch plus a pre-workout snack prior to the second workout.

Special Concerns: BCAA’s (branched-chain amino acids)

These are essential amino acids that play an important role in muscle metabolism. Leucine, as we’ve discussed previously, is needed to stimulate muscle protein synthesis. The are many BCAA supplements on the market that are advertised to athletes as “muscle building” with instructions to supplement this in liquid form (powder mixed with water) all day and during exercise. The research shows that consuming BCAA without other essential amino acids will not stimulate a maximal muscle protein synthesis response and should not be used to reduce post-exercise induced muscle damage.

There is no benefit to supplementing with BCAA in the context of a diet with adequate protein, so don’t waste your money.

Special Concerns: Soft Tissues and Collagen

Connective tissues (ligaments, tendons) are made of collagen proteins. Collagen helps to transmit the force from muscles and is essential for optimal performance. A few particular amino acids (hydroxylysine, hydroxyproline, proline, and lysine) in combination with vitamin C has shown to help improve collagen synthesis which is especially relevant for soft tissue injuries like ACL tears when taken 30-60 minutes before an exercise or rehab session specific to the site of injury. I’ve written more on that here, and I also teach about this in 1:1 sessions and my 6-week nutrition course for high level gymnasts and parents (and coaches/medical providers).

For the collagen protocol I use for injured athletes, click here.

Special Concerns: Meat Substitutes and Soy

From an anabolic perspective (muscle building), meat substitutes do not always provide the greatest array of muscle building amino acids. It takes more of these proteins to get the same effect as smaller amounts of animal proteins due to their digestibility and incomplete amino acid profile which confers to poorer bioavailability.

Meat substitutes like the Impossible Burger, Beyond Meet, or Garden meatless products are of made of soy proteins, pea protein, rice protein, grains, potatoes, fats, etc. They have an array of fats, starches, etc to hold them together and are flavored fats, salts, spices, and sometimes color (natural from plant extracts or added color). Pea, rice, wheat, and potato protein bioavailability is really poor. For a high level athlete, I wouldn’t depend on these meat substitutes as the main protein source in the diet; you’d be better of adding in soy (closest to animal proteins) or intentionally combining your own grains, beans, etc.

A food product like tofu or tempeh is made of soy which is a complete protein. These are not as bioavailable as animal proteins as only soy protein isolate (partially broken down) has 100% bioavailability. From my perspective, if an athlete is vegan it would be helpful to have some soy products specially around training to help with muscle repair, recovery. Soy foods are rich in B vitamins, fiber, magnesium, potassium making them valuable to the athlete with high nutrient needs.

There has long been concern about soy and its high concentration of isoflavones which is a kind of plant estrogen (phytoestrogen). Some worry that high intakes of soy overtime will cause issues with growth, digestion, sexual maturity, thyroid health, cognition, and cancer-risk. There are few studies backed by strong science to support most of these concerns. Part of the issue with the research is that studies all different in the population, type, and amount of soy (and how it’s processed, etc) which make the results not quite comparable.

From what we can tell, a serving or two of soy foods as day are likely to confer more benefit than risk, especially for those following a vegan diet.

In Summary

Hopefully this article has given you the information you need to ensure you, or your high-level gymnast, get in adequate protein for optimal performance and recovery. As always if you have questions feel free to shoot me a message. If you’re wanting individual recommendations, please reach out here. If you’re a coach or gym owner and want your entire team to gain a nutritional advantage, let’s chat about my Signature 4-Part Nutrition Series.

To not miss out on the latest gymnast nutrition blogs, sign up below to join the tribe.

on the blog